A 19th-Century Microsimulation

- Productivity windfall, human whiplash. Mechanized looms multiplied output 40×, yet they displaced hundreds of thousands of skilled hand-loom weavers and triggered decades of social unrest and wage collapse.

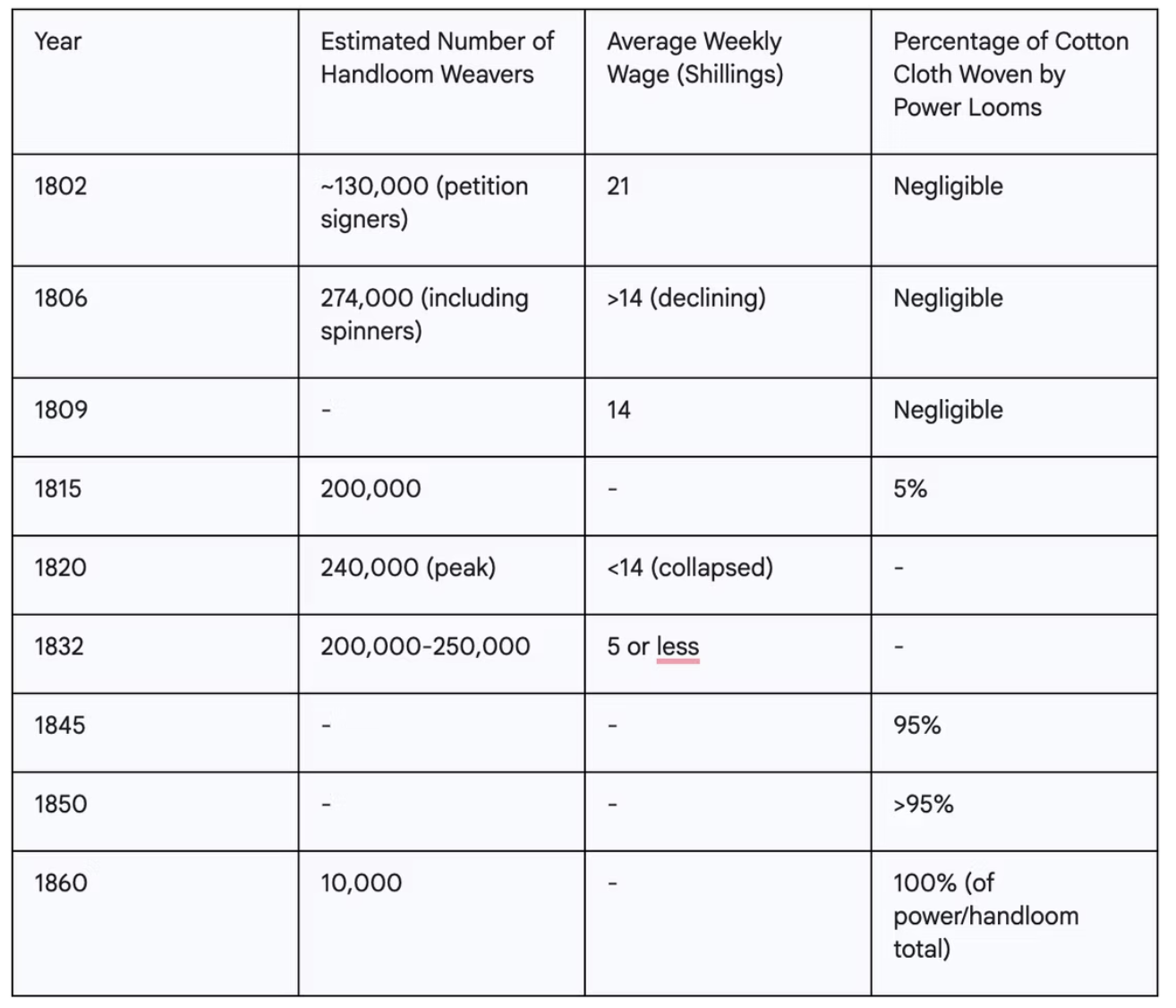

- From aristocracy of labour to poverty in a decade. Wages fell from 21 shillings to as little as 5 shillings a week; by 1860 only ~10,000 of the original 240,000 weavers were still plying their craft.

- Re-employment was slow, generational, uneven. Most displaced artisans never reclaimed comparable status; true absorption into new jobs took half a century and often skipped a generation.

- Skill “hollow-outs” hurt the middle most. Mid-skill crafts faded first, pushing workers either upward into white-collar roles or downward into low-skill factory labor—an early case of labor-market polarization.

Key Weaving Loom Innovations and Their Economic Impact (Industrial Revolution Era)

The sequence of key inventions in the textile industry during this period illustrates a dynamic interplay of challenges and solutions:

- John Kay's Flying Shuttle (1733): This invention dramatically speeded up the weaving process by allowing a weaver to pull the weft thread horizontally across the warp with greater ease and speed, enabling the production of wider textiles. It effectively doubled a weaver's output, creating a significant bottleneck in the supply of yarn, as spinning could not keep pace.

- James Hargreaves' Spinning Jenny (1764): In response to the yarn shortage, Hargreaves' spinning jenny mechanized spinning, initially allowing a single machine to spin eight threads simultaneously, later improving to 120 threads. This invention significantly increased yarn production, addressing the imbalance created by the flying shuttle.

- Richard Arkwright's Water Frame (1769): A further advancement in spinning, the water frame was a water-powered cotton-spinning machine that produced a much finer and stronger yarn than the spinning jenny, further enhancing spinning efficiency and quality.

- Samuel Crompton's Spinning Mule (1779): Combining the principles of both the spinning jenny and the water frame, the spinning mule produced even finer and more uniform yarn. This complex machine could measure up to 46 meters long and significantly increased the number of available spindles, with some models having up to 1,320 spindles, vastly increasing output.

- Edmund Cartwright's Power Loom (1785): This was the pivotal invention for weaving, initially water-powered and later adapted for steam power. The power loom doubled the speed of cloth production. While Cartwright's initial design was not immediately efficient, its theoretical principles were sound and continuously improved by subsequent inventors, laying the groundwork for mechanized weaving.

- Eli Whitney's Cotton Gin (1794): This invention mechanized the separation of sticky seeds from cotton fibers, dramatically increasing the productivity of raw cotton processing by a factor of 50. This ensured a vast and affordable supply of raw material for the burgeoning textile mills.

- Joseph Marie Jacquard's Loom (1801): Utilizing punched cards to control intricate patterns, the Jacquard loom was a revolutionary machine that allowed for very complicated designs to be woven. Its use of punched cards is widely recognized as a precursor to modern computer science.

- Richard Roberts' Loom (1822): Roberts invented the first cast-iron, steam-powered loom. Using iron instead of wood, as in Cartwright's earlier design, prevented warping and maintained constant yarn tension, significantly improving the machine's efficiency and reliability.

A Sea Change in Employment

So what happened to employment in this industry as a result, and how long did it take for workers to migrate and retrain for new roles in other sectors?

The advent of the mechanized loom, while a triumph of engineering, unleashed a powerful force of "creative destruction" that fundamentally reshaped the social and economic fabric of the time. This process, as described by Schumpeter, involves new innovations displacing older industries, leading to significant disruption and hardship for those whose livelihoods are rendered obsolete.

The advent of the mechanized loom, while a triumph of engineering, unleashed a powerful force of "creative destruction" that fundamentally reshaped the social and economic fabric of the time. This process, as described by Schumpeter, involves new innovations displacing older industries, leading to significant disruption and hardship for those whose livelihoods are rendered obsolete.

Handloom Weaver Employment and Wage Trends (UK, 1800-1850)

Why This History Matters Now

Four Loom-Inspired Actions for Leaders